My 'suit of armour' stammering analogy

Speech & language therapist Susie Lloyd writes about evolving from the 'stammering iceberg' and introduces us to an analogy of her own.

I find analogies extremely helpful in my work as a specialist in stammering. They can be so powerful if they resonate with a person, helping them see situations in a new light, and hopefully shining that same light on a path forwards too.

Analogies I often refer to include:

- The stammering onion. The idea that many layers can build up around a stammer like the layers of an onion, which can be peeled away. Stephanie Burgess has recently developed this idea further in her article 'Therapy explained through the stammering onion' on this site.

- The tightrope. The idea that the more you focus on not falling from a tightrope, the more likely you are to fall, just as the more you focus on not stammering, the more perilous a conversation will feel, and the harder talking can become.

- The finger trap. The idea that struggle and tension, a natural instinct to get out of being 'stuck', sometimes only serves to get you more stuck.

- The yard sale, which Vivian Sisskin uses on her 'Open Stutter' YouTube channel to imagine letting go of unhelpful patterns you have acquired around a stammered moment, but which serve no useful purpose for you.

However, it is the iceberg analogy that I, and so many of my colleagues, return to the most.

The stammering iceberg

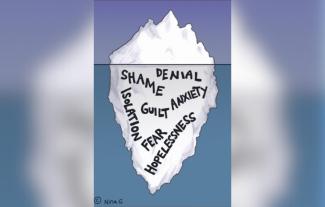

The iceberg analogy was originated by Joseph Sheehan in 1970 and it has become very widely used ever since. Sheehan wrote that "stuttering is like an iceberg, with only a small part above the waterline and a much bigger part below" (see Stuttering: Research and Therapy. New York, Harper & Row, on Google Books). The ice above the water represents the 'overt' part of a stammer, the part that is visible to the outside world.

The underwater block of ice represents the 'covert' part of a stammer that people don't see, which can often be much larger, densely populated by all manner of things that have been adopted in an attempt to anticipate, postpone, suppress or hide a moment of stammering. The underwater ice might also include difficult and painful thoughts and emotions that a person might experience in relation to their stammer, like anxiety, shame and fear.

Like many other therapists, I typically support a client to chart their own individual iceberg early on in therapy. Very often it becomes immediately clear that the stammer itself has become the tiny tip of that person's iceberg. The path forward, Sheehan highlighted with this analogy, is to focus on melting the body of the iceberg from below.

But over time, thinking around stammering has become more nuanced, and in some ways the iceberg analogy has struggled to adapt.

Limitations of the iceberg

In its original form, the iceberg simply existed, floating in an empty ocean. The analogy made no proper account for how it got there in the first place, focusing so closely on the individual and not on their circumstances. The impact of stigmatising and unhelpful experiences that cause people to develop these 'under the iceberg' features was not really acknowledged. In her recent book 'Stutterer Interrupted', comedian and author Nina G has taken the iceberg analogy forward by drawing our focus to the crucial temperature of the water surrounding the iceberg (read more in Nina's article 'Stutterer Interrupted' on this site). I found this particularly powerful, as expecting the ice to melt whilst still floating in the same freezing waters that formed it, makes no sense at all.

Thinking around stammering has become more nuanced, and in some ways the iceberg analogy has struggled to adapt.

Also lacking within the iceberg analogy was a sense of agency for the person who stammers; the story of why their iceberg built up underwater over the years. I'm thinking here particularly about the work of Chris Constantino and Hope Gerlach-Houck on the purpose of concealment, which thinks of the underwater ice not as a result of 'faulty thinking' or an excess of social anxiety, but instead as an active process — a form of protection which develops against very real and present stigma. And as a defence against ableism in terms of a world that perceives fluency as the norm. Listen to Hope talking about it on the Stuttering Foundation of America's podcast and read their article 'The Paradox of Concealing Stuttering' on the Redefining Stammering website.

The vulnerability that people can experience when trying to reduce the iceberg is also missing. An iceberg doesn't have feelings about whether it melts or stays frozen, after all. An iceberg is an object and therefore passive. It doesn't require courage to melt.

The Suit of Armour

All of these thoughts have led me to ponder on what metaphor might work better for me and my therapy clients, and I decided on a Suit Of Armour. The ideas that I hope this analogy captures are:

Protection

It is a completely natural human instinct to want to protect yourself from unhelpful, uncomfortable and painful reactions and attitudes to stammering. Different pieces of armour can represent the different 'covert' ways a person might have sought to protect themselves, such as beginning to hold back, say less, scan sentences ahead and swap in different words. They might pretend to forget words or ask for the things they feel they can say fluently rather than the things they want, use pre-scripting, backtracking, fillers, and so on. These things might be represented by a helmet, a breastplate, gloves, a shield — a growing suit of armour that starts small but gets more and more elements added to it over time. Initially, doing all this can make a person feel less vulnerable, more protected and safer from stigma, but...

Armour downsides

Wearing a suit of armour comes with huge inherent problems. Problems that are analogous to dedicating a vast amount of physical and mental energy to hiding stammering from others:

- It is heavy to wear, requiring constant effort to maintain it, which is exhausting. Relaxation becomes impossible in a suit of armour. This accounts for the massive sense of burnout that so many people who stammer tend to feel.

- It is stiff and inflexible, restricting a person's freedom to move freely through the world, making it extremely difficult. They might begin to make important choices around maintaining an appearance of fluency or minimising the chances of stammering rather than going for what they really want in their careers, relationships, social lives, and dreams and aspirations. They can only move as far as their armour will allow.

- It also makes spontaneous communication impossible. The very barrier that a person uses to protect themselves can get in the way of them communicating with others, just like trying to speak and be heard through an armoured helmet. An example might be someone feeling the need to stick to minimal talking, or censoring themselves for potentially stammered words. Or holding back on their own ideas and contributions in a conversation, at the cost of all that is left unsaid.

- It can also act as a barrier to connection with others. This can prevent you from feeling present and prevent others from seeing and getting to know the real, authentic, you — the one that lies beneath the armour. For example, people who are by nature chatty, friendly and sociable, but might be perceived as shy and reticent due to the wearing of the armour. As Chris Constantino said in his Tedx Talk 'Stuttering, Vulnerability & Intimacy', which you can watch on YouTube, "authenticity and intimacy with others necessitates a level of vulnerability".

People of all ages that I have worked with have, with tremendous courage, shed some of that armour, and have felt so much lighter, freer and happier for it.

Vulnerability

However, making the decision to take off the armour can make you feel extremely apprehensive and vulnerable too. Especially if you have been wearing it a long time, or if you are still surrounded by those difficult reactions and attitudes that you wanted to protect yourself from in the first place. It can leave you feeling defenceless, disarmed. It is not an easy choice, although as a therapist I know that it is one well worth making.

Removing one piece at a time

But, as with a suit of armour, it doesn't have to come off all at once. You can take it off slowly, one piece at a time. And you can make an individual choice about the circumstances that you as an individual would feel safe to do so in. You can also plan what form of support needs to be in place for that to happen. Whether that is from the people in your life, from therapy, from the stammering community, or all three.

I hope that this analogy is helpful. I know that people of all ages that I have worked with have, with tremendous courage, shed some of that armour, and have felt so much lighter, freer and happier for it. But ultimately, I hope for a future that is free of stigma around stammering, so that no one ever feels that they need to take up any armour in the first place.

I am not a person who stammers and so I would be extremely grateful for any feedback on whether this analogy resonates with your own stammering journey. Email STAMMA at editor@stamma.org and they will pass it on to me.

Thanks to the therapists from my local Yorkshire and Humber Stammering Clinical Excellence Network, for their encouragement and the invaluable feedback from their own service users on the idea, and to my own service users who shape my practice. And to the volunteers, kids and teenagers of the recent STAMMA Family Day in Sheffield!

And thank you to STAMMA for supporting such discussions.

Susie Lloyd currently works as a Highly Specialist Speech Therapist in Stammering for Bromley Healthcare CIC, and in private practice.

Read more Your Voice articles. Would you like to write one? See Submit Something For The Site or email editor@stamma.org for details.