Stutterer Interrupted

Read a whole chapter from US-based Nina G's new book 'Stutterer Interrupted: The Comedian Who Almost Didn't Happen', about how she changed her thinking around stammering. First up, here's an introduction from Nina herself...

My entire life I have adored stand-up comedy. While other girls my age were fawning over New Kids On The Block, I was crushing on comedians I saw on TV. In my comedy nerd-dom, this made me want to be a comedian. This dream died, however, when I was a teenager because I didn't think someone who stutters like me could be a stand-up. My attention turned to other things.

This changed in my 30s after I attended a conference for people who stutter. I realised how much I had been holding myself back; not because of my stutter, but because of how I thought about it. I began to shift my perspective and within months I picked up my dream to be a comedian and got up on stage.

My newly-released book, 'Stutterer Interrupted: The Comedian Who Almost Didn't Happen', chronicles my relationship with stuttering and stand-up comedy. The following is a chapter from my book that more closely examines the shift in how people who do and don't stutter can question and possibly shift how they think about stuttering.

(Ed.: a word of warning — the following contains a few minor swearwords.)

Chapter 19: Transforming The Iceberg

I have very little control over my stutter. I wouldn't even call it control; it's more like I have to bargain with it. "Hey Nina's Stutter, if I put on my 'business voice' and totally not sound like myself, will you let me get through this one phone call with a stranger?" "If I avoid this word or that word, will you at least stay out of my next sentence?" I get exhausted just thinking about it. If I planned my day around Nina's Stutter, there wouldn’t be time for anything else. Life is short, and I'm not going to waste it trying to control what I can't control.

Stuttering is one of the few constants in my life. My hair has changed, my clothes have changed, my address has changed — but Nina's Stutter is here to stay. It has never changed, and it probably never will. But the way I think and feel about it has changed.

I used to hate Nina's Stutter. I was ashamed of it. I devoted the best parts of my youth to fighting it, instead of doing what made me feel happy and productive. The more I missed out on life, the more I blamed Nina's Stutter, doubling down my efforts to kill it. If only I were fluent, everything else would fall into place! I could speak freely. I could have boys ask me to prom. I could even follow my dreams and be a stand-up comic. All I had to do was stop stuttering!

When I write it down, it seems so ridiculous. How can some pauses and a few extra syllables take control of a person's entire life?

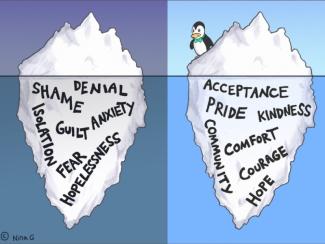

That question became a point of focus for Joseph Sheehan, a clinical researcher and psychologist. Throughout his career, he observed that stuttering was typically more disruptive to a person's emotional wellbeing than it was to their actual speech. In Stuttering: Research and Therapy (1970), Sheehan writes that "stuttering is like an iceberg, with only a small part above the waterline and a much bigger part below." According to Sheehan, what most people think of as "stuttering" is only the tip of iceberg — the outwardly observable symptoms on the surface. But the emotional baggage that comes with it — the invisible pain underneath — that's where the bulk of the ice really is. Sheehan organized these murky, underwater emotions into seven categories: fear, denial, shame, anxiety, isolation, guilt, and hopelessness. According to Sheehan, as the stutterer resolves these issues, the negative emotions begin to "evaporate." This in turn causes the "waterline" to lower, until, finally, all that remains is the physical stutter.

Sheehan's book became highly influential in its field. The iceberg theory advanced a more holistic view of stuttering, inspiring professionals to consider more than just the sounds coming out of a person's mouth. It also helped me think about my own experience. I know all about those emotions below the water. I have felt guilty for making people wait through a stalled sentence. I have felt isolated, especially before discovering the stuttering community. But most of all, I have felt shame, simply for speaking the way that I speak.

Although it provides a useful framework, I don't think Sheehan's Iceberg presents the full picture. Sure, it explains the negative things we feel, but what about the other emotions? Just like everyone else, the life of a stutterer is filled with ups and downs, victories and defeats, good times and bad times. Even if your overall situation doesn't change, things might look better or worse on a given day depending what side of the bed you wake up on. It's all a matter of perspective.

If you've ever lain on the grass and looked up at the clouds, you know how easily perspective can change. One minute this cloud looks like a dragon; the next minute it looks like a bunny rabbit. Unless El Niño is brewing up an apocalyptic tornado, that cloud probably hasn't changed much in the last sixty seconds. Instead, you let your eyes wander, reoriented your perspective, and unknowingly formed a different mental picture of the same thing.

If it can be done with literal clouds, then it can be done with metaphorical icebergs. Stuttering doesn't have to be a bad experience if we change our perspective. Before I found the stuttering community, my perspective was all negative. I was isolated, ashamed, and everything else Sheehan packs into that sad popsicle. But when I found the National Stuttering Project during that summer in high school, something changed. I was no longer isolated — I had found a community. I was no longer ashamed. Maybe even… proud?

Sheehan writes about negative emotions evaporating until only a stutter remains. I disagree. When bad feelings subside, other feelings have to take their place. We don't refer to happiness as "not sadness," or confidence as "not embarrassment." The negative emotions in Sheehan’s Iceberg all have positive equivalents. I propose that we can do more than simply make the bad feelings go away; we have the power to transform fear, shame, anxiety, isolation, denial, guilt, and hopelessness into feelings of courage, pride, comfort, community, acceptance, kindness, and hope.

So how do we do that? Although the negative emotions in Sheehan's Iceberg are common to the stuttering experience, they are common because we live in a society that treats people with disabilities as sub-standard. But we don’t have to buy into it. All the weird looks we get in public, all the shitty images we see in the media, all the lowered expectations that people project onto us — they can all be thrown out and replaced with something better. Instead of struggling to conform to the ideals of a culture that makes us feel deficient, we can cultivate our own perspective and learn to love ourselves as we are. Every person who stutters has the responsibility to create their own iceberg — one that reflects their best possible self.

How we are perceived is largely influenced by how we perceive ourselves. When I began to accept my stutter, so did the people around me. Friends and family stopped offering advice on how to improve my fluency. People stopped thinking of me as a weirdo (at least after high school). Obviously, there is a limit to how much self-perception can determine the views of others: I can’t force an asshole to stop being an asshole, as we've seen countless times in this book. But I can determine my own worth and decide which assholes are beneath me. I can share my values with the world, doing what I can to sway us from that asshole culture toward something more loving and equitable.

Promoting stuttering acceptance has been one of my greatest missions in life. Everyone who interacts with us, thinks about us, studies us, works with us, produces movies and TV shows about us, reports on us—they all have stuttering icebergs too! Just like Sheehan's model, the strange and shitty ways they treat us are just the tip of the iceberg, stemming from murky emotions beneath the surface. If we are ever going to overcome discrimination, we have to address the emotional baggage of these people as well. It's not going to be easy. It's hard enough to understand my own feelings toward stuttering, much less model them for others! All I can do is put myself in front of the public and try my best — in bars and comedy clubs, on college campuses, in online videos and social media, and now on in this book. Changing minds isn't easy, but I’ll take that over trying to change who I am.

Want to read more? Nina G's book 'Stutterer Interrupted: The Comedian Who Almost Didn't Happen' (published by She Writes Press), is out now to buy on paperback and e-book from Nina G's website. Follow Nina on Twitter: @ninagcomedian