Sparrow Harrison & the birth of our charity

Our co-founder Sparrow Harrison MBE tells us his story, from his schooldays with a famous classmate to the chance encounter that led to him starting an organisation for people who stammer. Let's go right back to the beginning…

When I was born my parents told my older sister, then aged six, that I was going to be called Robin. She said to them, “He looks more like a Sparrow”. It was a nickname that stuck with me all my life.

When I was seven, I went to boarding school and started at the same time as a boy called John Ravenscroft, who later went on to become the famous DJ John Peel. Around that time I was developing a stammer. I remember not being able to read extracts in class as the other boys did. I was down to represent the form by reading a passage at a Christmas service, but John was asked to read it instead.

Going into my teenage years I wasn't too worried about my stammer. That was until girls became part of my life. Then I became quieter and quieter. Self-confidence was something I didn't have, which made growing up difficult. My family were worried too. I came from an army family; my father was a colonel and both grandfathers were generals. One of them, on my mother's side, gave me a pair of boxing gloves so that I would learn to be a man! I learnt to box, and it's something that became very important to me. It gave me street-cred. I thought it would make up for looking a bit of a fool because I stammered by learning to be tough. In his memoir, John Peel said that I used to protect him from bullies. In those days there was a lot of bullying.

...I went to the bottom of the pile and did many different jobs that didn't need oral communication.

As I went through boarding school I really did seem to have a talent with boxing. Back then most schools taught it and had competitions, and I did pretty well at them, even beating someone who had never been beaten before. I wasn't much good at anything else — I was hopeless in lessons and not much good at other sports.

Marching into the army

My family were still worried about my stammer though. They sent me to all sorts of psychiatrists and people who said they could help me with all kinds of mad ideas, but to no avail. In those days there was very little understanding about stammering, even though the King himself stammered.

I followed my family's footsteps and went into the army. I wasn't much good as a soldier but boxing kept me in and I got into Sandhurst by going through the ranks. However, my military career came to an abrupt end when I had to drill a squad and I couldn't say "Halt!". I just couldn't get the word out. The squad would still be marching now but for the wall that stopped them! Nowadays, the army is much more understanding of stammering, so I hear, but in those days I had to leave because of it.

Moving to Swinging London

Having a severe stammer made life difficult. With oral communication being so important, I felt it was hard to maintain respect if you weren't fluent. So when I left the army I went to the bottom of the pile and did many different jobs that didn't need oral communication, including as a labourer in a Liverpool factory. In search of a more exciting nightlife I then travelled south and found myself in the middle of London in the Swinging Sixties, where I found a job as a gardening labourer before then becoming a minicab driver. My call sign was 'Baker 5' — not great when I struggled to say words beginning with B.

As I didn't stammer when I sang, I used to love singing and playing the guitar. I was into R&B, blues, country, rock and roll… in fact all music. I wasn't very talented but with a few friends I started a group called 'Sparrow and the Gossamers'. I found I could speak fluently when I wasn't speaking to anyone directly, so at gigs I would address the whole crowd over the microphone, introduce numbers and be the band's spokesman. We got around, even playing on the same bill as Tom Jones, P.J. Proby and Alexis Korner. Alexis actually brought the Rolling Stones, then at the start of their fame, along to watch us. We even travelled to Germany to play. However, we were nothing special and eventually broke up, but we stayed friends.

The birth of the AfS

So how did I go from that to starting up a national charity? It all started when the son of a family friend, who was at Eton, told my mother about a man called Henry E. Burgess, who was touring private schools teaching pupils who stammered techniques to manage it. Burgess got in contact with my mother and offered to help me. My mother paid a substantial fee for him to take me on. So I went to see him a few days a week whilst working in a garage on the other days. He used a method known as the 'Wings' method, after a man called Raymond Wings, where you lengthened vowels and used a humming sound to get words out, amongst many other techniques.

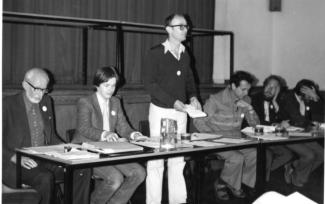

Knowing that I was looking for a different job, Burgess invited me to help him teach others these ways to deal with stammering. So I started going with him to the private schools. After a while, Burgess's health started to deteriorate and he eventually went into a home, so I had to take over and run things myself. Sadly he died in 1978 and I was left holding his stammering empire. I thought long and hard about what I would do with it. I didn't want to continue Burgess's business of charging a lot of money and offering a cure, as I knew there was no cure for stammering. Eventually I decided to make it into a free self-help association, where people who stammer could practise speech techniques and get advice. I ran group sessions using what I had learned to help others and I called it the 'Association for Stammerers' (AfS).

Burgess died in 1978 and I was left holding his stammering empire. I thought long and hard about what I would do with it...

I used to run meetings from my flat in central London, which I shared with five other people. I remember persuading a policeman, who came along one day to see me about a parking offence, to speak using the techniques, even though he didn't stammer. He didn't stay long and I don't think I had to pay the fine. Eventually, I encouraged group members to start running the sessions, letting them take it in turns. It was an honest but amateur group which, I hope, helped many stammerers.

One day a speech therapist called Peggy Dalton came to one of our meetings. When it finished we started talking and she told me she wanted to set up a national charity for people who stammer, with the help of speech therapists, and suggested working together. I immediately realised that this was what I had been wanting, so after I spoke with the AfS committee, we agreed and joined forces: Peggy as Speech Therapy Adviser, taking over the running of the association, and me becoming the Chair. She gave the organisation the respect I don't think I could have given it and it made us into a much more successful organisation. Our secretary Craig Dunant, together with General Editor Lionel Halter, deserve praise too for shouldering nearly all the work of getting the Association going.

Just not cricket

1981 was the 'International Year of the Disabled' and I was invited to Buckingham Palace in recognition of starting the association. That same year, a high profile cricket match was arranged in Oxford between the AfS and a team made up of blind players. I was not a very good cricketer but I had captained the team a few times. When we usually did the coin toss to decide who batted first, I used to pretend I was stammering while the coin was in the air so that I could make my call when it landed and I saw what it was — I always used to get away with it. But when I did it again that day, I realised I had taken advantage of the opponents' blindness. But they wouldn't change it, however much I tried.

I remember we played with a football-sized ball which had metal fillings inside so that it made a noise the blind players could hear as it travelled through the air. We had a problem in that when we were bowling, we had to shout "Are you ready?" followed by "Play" once the batter indicated their consent. After long overs of batsmen waiting to be asked if they were ready — us being stammerers — and then finding the ball had gone past them when the bowler eventually said "Play", it was decided that the umpire would do the shouting.

We were on the way to being thoroughly beaten when the groundsman came to our rescue as he wanted to go home for the night. I told him we wouldn't hold him up, so we were able to declare the match a draw, much to our relief.

Post-AfS

I gave up chairing the association after about 10 years, with Ron Turrell taking over from me. Although we were very different characters he was just the right man for the job and played a very big part in keeping it going after I left.

In 2015, I paid another visit to Buckingham Palace when I was awarded an MBE in recognition for my charity work, including setting up the Cae Dai Trust and also the Denbigh & District Amateur Boxing Club. My love of boxing stayed with me through the years and I wanted to give something back by starting a club that gave young people the confidence it gave me.

Looking back, I'm so pleased that this charity, which started as the AfS before changing its name to the British Stammering Association and then STAMMA, has gone on to reach the success it has now. I feel that so many people have given time and effort to keep it going, and their memory fades as time moves on. At 86, I'm happily living with my partner Gemma (pictured) in North Wales, and I'm a curator at the Cae Dai 1950s Museum in Denbigh, which is where I'm standing in the main picture. I sometimes think people don't realise I am still alive. I am — not so much 'kicking', but certainly 'twitching'!

A huge thank you to Sparrow for sharing his story and for all he's done for the stammering community over the years. Salute to you Sparrow! Do you have memories of our early days? We'd love to hear about them — see the blue box below.

Share your memories & photos

Were you a member in the early days of the AfS? Do you have memories or photos from the late 1970s and '80s that you'd like to share? We'd love to hear from you!

At our next conference in 2026, we'd like to put together an exhibition to display your stories and photographs. We want to show our members how it all started and remember the people involved. Let's keep the history alive.

Please email us at editor@stamma.org or post your stories and/or scanned photos to: STAMMA, Box 140, 43 Bedford Street, London WC2E 9HA.