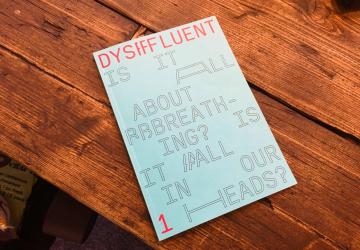

Dysfluent magazine

Dysfluent is a brand new magazine exploring experiences of stammering. We caught up with its editor Conor Foran to find out more.

*Update August 2025: Conor's magazine Dysfluent is being featured in an exhibition at the V&A called Design and Disability. The exhibition runs until 15th February 2026.

Hi Conor, Tell us about dysfluent

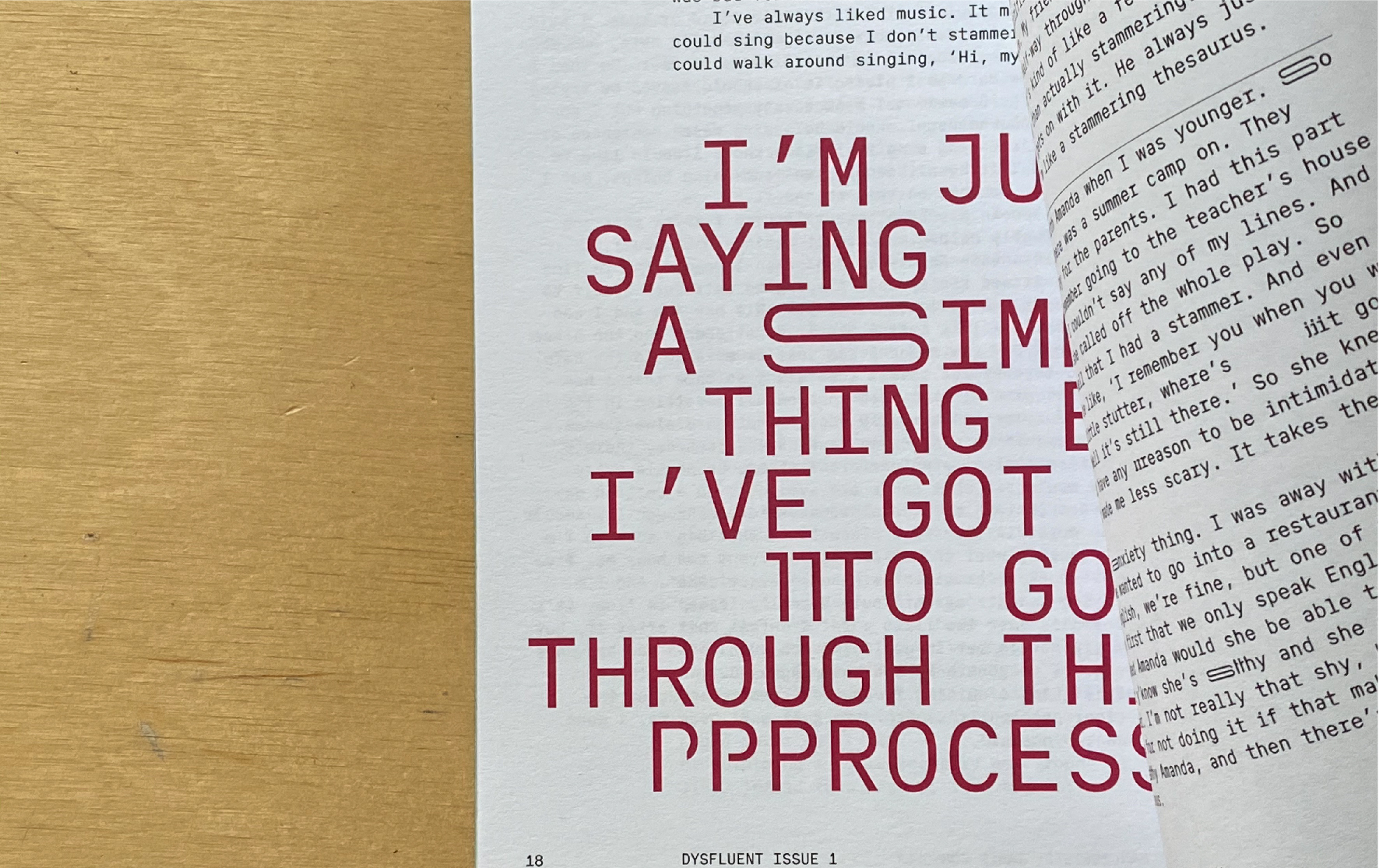

Dysfluent is a magazine that aims to strip away the academic and clinical explanations of stammering and instead replace them with everyday honest and relatable stories through interviews with people who stammer.

It's a way to define and label dysfluency. By recognising stammering as a strength and de-stigmatising it as a weakness, it becomes something to be proud of.

I wanted to explore the topic in a new way — to give stammering a home and identity that would be seen by people who don’t stammer.

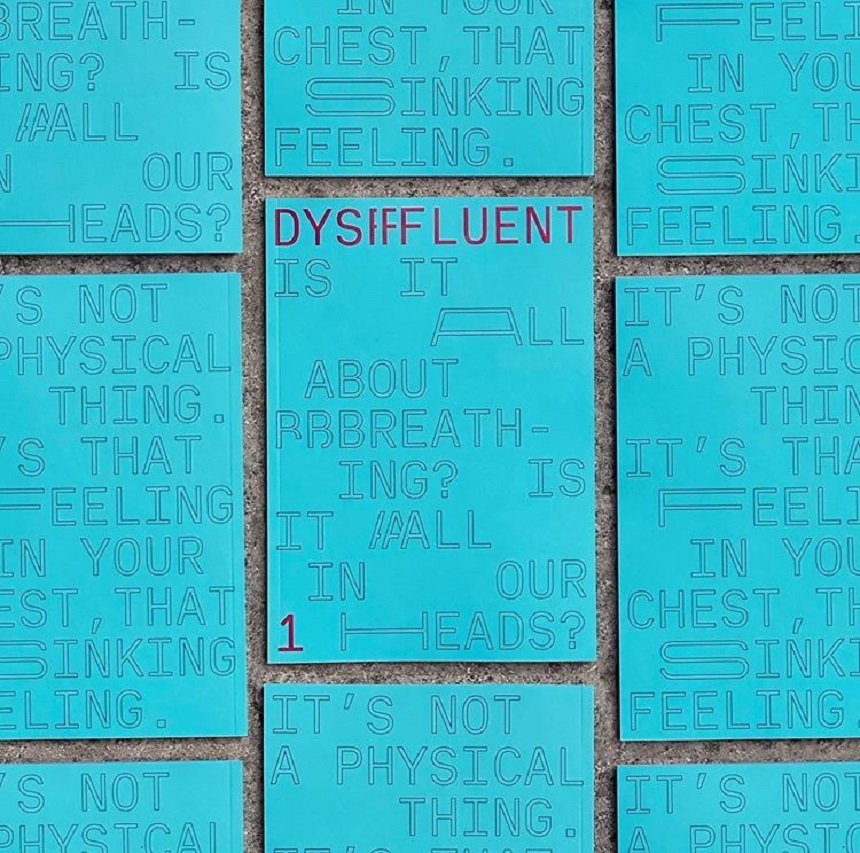

The typeface used throughout the magazine represents the voice of the stammerer. Its letterforms stretch and repeat, giving stammering an identity and something to take ownership of. This concept of identity is present throughout.

All copies of the first run have sold out which is incredible, and I'm currently getting more copies printed due to the demand. I’m not making any profit from Dysfluent at all.

How did Dysfluent come about?

Dysfluent began as a final-year college project three years ago. I originally wanted to call it 'The Curious Paradox', after the psychologist Carl Roger's famous quote about acceptance: "When I accept myself just as I am, then I can change."

It really started as a way to understand myself. As a person who stammers, I am still trying to figure out how it defines me. Some people might not agree that it can or should define anyone, but I think accepting it as something that you cannot change gives you the power to leave all the negativity and stigma behind.

Who is Dysfluent aimed at?

Dysfluent is aimed at people of all ages who stammer. We may experience similar things, but each story is unique.

It’s also aimed at people who don’t stammer; I don’t want the magazine to exist within a ‘stammering bubble’ — It’s got to be seen and read by people outside of our community so they know what it’s like to stammer. This is why I hope Dysfluent will be on shelves alongside other magazines. Who knows who could pick up a copy? Who knows what they could learn?

Why a magazine rather than a website?

There is the possibility for Dysfluent to evolve into a website, but as a starting point I really wanted to bring stammering into a new space, a new format. There are so many amazing websites out there for people who stammer; in order for Dysfluent to stand out I wanted to explore the topic in a new way — to give stammering a home and identity that would be seen by people who don’t stammer.

It’s even won design awards, hasn’t it?

In the early stages it was awarded by multiple organisations such as D&AD, the Best British Book Design and Production awards and the Institute of Designers in Ireland for its design and typographic explorations. While these did help it get recognition, it was always a personal endeavour to continue the project.

What have you learned from making it?

Many things! learned there’s so much support out there. It’s a really interesting and exciting time to be neurodiverse. As our society becomes more accepting of different cultures and ways of life it’s only right that neurodiversity is celebrated as a positive variation rather than a negative.

Creating Dysfluent taught me that being a minority brings with it an inherent sense of activism. Because there’s a possibility I might be the only person my co-workers or friends know who stammers, I think it’s so important to represent it well. It’s our job to educate those who don’t live with a stammer about what it’s like to live with one. Otherwise they learn from the media, which may not portray us in an accurate light.

It’s a really interesting and exciting time to be neurodiverse.

I’ve also learned how great and reactive the stammering community is around the world. People who stammer deeply care for those in their community. It’s a reactive and ever-growing forum that welcomes interesting conversation and challenges to that conversation. We all want to know why we stammer, how it defines us and how we can deal with it — we’re all in it together, and creating something like Dysfluent is exciting as it definitely adds to that conversation.

It’s also showed me how curious people who don’t stammer are. I’ve had so many conversations about the magazine with people who really just want to understand it all. Working on Dysfluent has made me open up a lot to these kinds of people, and I think we as people who stammer should all be as honest and approachable as we can, because in the end it makes our everyday interactions easier.

Has your relationship with, or view on stammering changed?

It’s changed a huge amount. Meeting people who stammer has made me reflect on my own life. The first person I ever met who also stammered was James Connolly, whose story’s in the magazine. James is the same age as me and talking to him was like talking to myself — we had the same behaviours regarding our speech and I found that fascinating.

Creating something like Dysfluent is exciting as it definitely adds to the conversation.

Publishing each interviewee’s story has allowed me to better know myself. Because we all share such similar experiences, it confirms we aren’t all those negative things we tell ourselves, like being incapable or incompetent — at least not more than any other person (to paraphrase speech-therapist Dr Joseph Sheehan).

I realised I can more easily talk about stammering and my own experience with it. Dysfluent has been my coping mechanism — my therapy.

What do you hope readers get from the Magazine?

Above all, I hope Dysfluent dispels the perception that a person who stammers is weak, stupid or incompetent. In the media, stammering is seen as something to be overcome, or as a trait that suggests the person to be a liar or a schemer. I want readers to connect with the interviews in the magazine and realise that although they are about life with a stammer, they’re also about what it means to be human.

What are your future plans?

I think getting more organisations involved is one of the next steps. I want Dysfluent to be seen and read by as many people as possible.

The topic of the next issue has been decided already: gender. More men than women stammer. What are the emotional implications for men who stammer when society tells them to be ‘macho’? Do women feel mis- or under-represented in our community? There’s a lot to be said. Dysfluent is having a call for contributions on this topic, so send me an email (via the address below) if you have any ideas.

Considering stammering as a disability is something I want to explore in future issues as I think it’s part of a broader conversation about not only stammering but how we view disability as a society.

Dysfluent is out now and you can get your copy at www.dysfluentmagazine.com

Email Conor at hello@dysfluentmagazine.com or find him on Twitter/Instagram: @dysfluent