How my stammer saved my brother & me

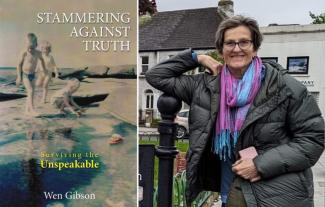

Wen Gibson's autobiography 'Stammering Against Truth: Surviving the Unspeakable', details her early life with a stammer and the harrowing child abuse she suffered. In this article telling the story behind the book, Wen describes her speech & language therapist's theory about how she might have used her stammer to protect herself.

Warning: Wen's story contains details of child sexual abuse that might be triggering for some. You can read more about the book in our review written by Christine, from the Women Who Stammer Support Group.

I hated my stammer as a kid and young adult. I was criticised and laughed at. My pain was silent when faced with a world of fluent speakers. I felt isolated, alone and unseen.

People often mimicked my stammer back to me, smirking into my face, especially my mother. She was cruel and gloated when I got stuck. I went mute when she walked into the room. Only with my twin brother Graeme and older brother Trevor, did I talk freely. We made up our own language which the adults couldn't understand. I can't remember if I stammered on those words.

My grandmother was the first gentle adult I met. She listened to me carefully. She didn't butt in, attempt to say things for me or tell me I was stupid. For a long time I equated my intelligence with my inability to force words out.

Protective mechanism

The first therapist I had was okay when I first started working with her, but gradually she grew impatient when I got stuck on words. She accused me of "hanging onto my stammer". This was in the late 1980s in Scotland when people still thought stammering could be cured. She told me I didn't want to grow up. That I wasn't trying hard enough. She demanded to know what I was avoiding and to stop this stammering nonsense. If only!

Kay was the first person who suggested that maybe my stammer grew from a disability to a protective mechanism; that it was protecting me from my father.

The more she bullied me the more I stammered, until my words dried up, just as they had with my mother. When she started picking on my relationship with my twin brother, I finally stood up to her and told her she was a bully. I left her and found a wonderful, kind therapist, Kay. Kay was the first person who suggested that maybe my stammer grew from a disability to a protective mechanism; that it was protecting me from my father.

As a child, my father threatened me physically. He carefully watched and listened to any words I might attempt. He was making sure I didn't say the words that named what he was doing. When I stayed silent, he nodded and smiled, but his eyes were cold and his mouth was a tight grimace of promise of what he would, and could, do.

Kay told me how she thought my stammer gave me time to notice any naming words that might be escaping — to catch them in the hesitant sounds — and change them to something more innocent. This stopped my father from carrying out his very real threat of killing me and my twin brother. That is how my stammer saved our lives.

Me and my stammer have become buddies. I listen to her when she gets stuck: she's my early warning system of approaching danger.

I now have a much softer relationship with my voice. Yes, I still get stuck, especially if I'm tired. Then, it's easier to write than speak, but I can and do speak up now. Me and my stammer have become buddies. I listen to her when she gets stuck: she's my early warning system of approaching danger. My stammer is brilliant at picking up threat, stammering more when I'm not safe.

Naming words of any kind are especially difficult for me to say. They are the words I was not allowed to speak. They still hint at threat and hold the terror of my frightened child place.

What's much easier to say are emotional words. I'm almost fluent with them. I'm aligned and honest and real. My voice is mine. I can say what I want.

My book

Writing the book 'Stammering Against Truth: Surviving the Unspeakable' has set me free. I have named my stammer as my friend. She is now upfront and out there in the world for all to see. I'm celebrating her and saying thank you. Thank you for keeping me and my brother safe.

The book started as a series of poems in 1990. It's taken me until now to find the words between the poems. One of the first pieces I wrote is the following poem. It was included in The Zero Tolerance of Violence Against Women and Children Conference in Edinburgh in 1992.

A Private Torture Made Public

By Wen Gibson

You probably don't realise

What it means for me

To have my words read aloud.

This is not just the reading of a poem

This is my life, my torture, my shame

Shown to you.

I've been forced close to death

To keep exactly these words hidden

So if I tremble as you listen, my cheeks burning up

Yet I smile

It's only to cover the shattering of a message

Etched finely inside

Under layers and layers of years.

I tell the full story of my struggle, searching and finding, in the recent publication, 'Stammering Against Truth: Surviving the Unspeakable'. My book comes with a content warning as it contains trauma and distressing events, but is ultimately uplifting and full of hope — a way to heal. It has also been made into an audiobook, and because it's audio, the more confronting scenes have not been included. The narrator, Sarah Armanious, had done a wonderful job of speaking my voice, stammer and all.

'Stammering Against Truth: Surviving the Unspeakable' by Wen Gibson is out now on paperback and ebook, available on Amazon, and audiobook, available on Spotify, Kobo and Google Play. Read our review to learn more about the book.

If you have been affected by anything you've read here, you might like to join the Women Who Stammer Support Group. There you can get support and talk about your experiences. Or you can call our free helpline on 0808 802 0002, or start a webchat.