Book Review: The Perfect Stutter

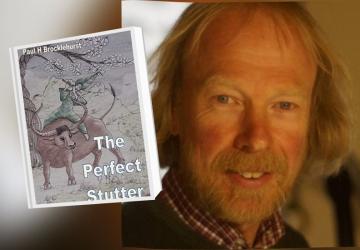

A review of the book The Perfect Stutter by Paul H. Brocklehurst. Reviewed by STAMMA Member Jack Nicholas.

Paul H. Brocklehurst is known to readers of the STAMMA website, with his article Stammering and Post-traumatic Stress — Food for Thought and the listing for his Stammering Self-empowerment Programme course. His self-published book, 'The Perfect Stutter' expands on these ideas and much, much more, asking difficult questions and arriving at unexpected answers.

It is a book of two interleaved parts written at different times of the author's life, mixing his personal experiences and thoughts as someone who stammers with analysis of different theories of and approaches to stammering. Part one is a memoir, an account of his life with a stammer from childhood to middle age. He is clear and devastatingly honest as he talks about his relationships with family, friends, partners, children and employers — and always near the surface of any interpersonal relationship is his internal, intense and deeply personal relationship with his stammer.

As perhaps for many people who stammer, Brocklehurst's stammer is almost an alter-ego: an unpredictable, often unwelcome daemon sitting on his shoulder, altering his life's path at every turn until, in time and after deep thought, he is able to change how he thinks and works with the 'perfect' stutter.

Part two is a review of some of the current thinking in a host of related areas: speech and language therapy, the chemistry and neurological pathways of the brain, theories of language and psycholinguistics. He is trying to tease out the causes of stammering and from there any possible approaches to it.

The two parts are not as clearly delineated as the author suggests. Part one uses personal experiences and part two is scientific in mood — the two parts mirror each other.

As someone who stammers but has no professional or academic knowledge of the subject, the explanations of different hypotheses such as EXPLAN (see researcher Peter Howell's article on the UCL website) and the Covert Repair Hypothesis (see the PubMed.gov website for an explanation) are, to me, clear and convincing; parts of the brain that generates speech get out of sync with the parts of the brain that produces the sounds of what is being said. Paul then relates these ideas to the Vicious Circle Hypothesis, which suggests that people who stammer become sensitive to their speech and hyper-vigilant in trying to correct and monitor it.

The descriptions and analyses of the theories are supported by a wonderfully eclectic list of references for further reading ranging from Van Riper's classic texts on speech therapy to Pirsig's 'Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance' — it is a shame that there isn't an index as there is so much here to reflect on.

The Perfect Stutter is difficult to categorise. It is not a misery memoir, nor a text book, a manifesto for changing society, or an easy reassurance that all will be well. Neither is it a self-help book. It swims against many tides!

It is perhaps best described as what modern anthropologists and sociologists call 'autoethnography' — a rigorously honest examination and description of the author's own life, experiences, thoughts and feelings all then related to wider questions about stammering and its relationship to individuals and society.

Brocklehurst's account is of a life that many people who stammer will recognise: isolation, cycles of therapy, hope and disillusionment, searching for understanding of what a stammer is and why it sits on your shoulder, shaping your life — and finally, the bravery of working through all this and creating a life, jobs and relationships. And through all of this, understanding more of yourself. For example, this moving reflection:

"And, despite being in a loving relationship, I still felt lonely and isolated. In the past I had attributed this feeling to my stutter and my difficulty communicating. But now that my speech was to all intents and purposes fluent, it was becoming increasingly clear to me that much of it was because I was just not like most other people."

Paul asks difficult questions of himself and others and is unsparingly honest in his answers. I am not sure if he gets all the answers he's looking for — I am not sure we can get those answers at the moment — but his search is a delight.

Some of his answers are his gut feelings — a finely attuned gut based on self-examination, practical research and theoretical inquiry. And those answers then become gauntlets, thrown down; new questions for further research.

The search for understanding runs through the book. Unspoken but loud is the realisation that anyone can come up with a theory about stammering (and over the years many societies, academics, therapists and stammerers have done just that), but proving a theory is a different matter entirely. In Brocklehurst's account, it seems that today we are not trying to find the

needle in the haystack, but the slivers of mental metal from which to piece together the needle. This is exciting, but slow, difficult work.

Alongside this work, Brocklehurst explores a very different thread: mindfulness and our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world. This is not unique to him. Mindfulness is a core component of speech therapy courses at London's City Lit, for example — but the author discusses and is greatly influenced by ideas in Zen philosophy.

And herein lies both an unexpected answer and the title of the book. A stammer can help you understand who you are, and who you have the perfect right to be.

The Perfect Stutter stays in my thoughts and encourages further reading and research. More, as a stammerer, it encourages personal reflection and honesty.

The Perfect Stutter, by Paul H. Brocklehurst, is available to buy in paperback and Kindle via Amazon.