My notoriety meant no one noticed I could hardly speak

Update 23rd May 2025: We're very sad to share that Mark has sadly passed away aged 59. We're reposting it here as a tribute.

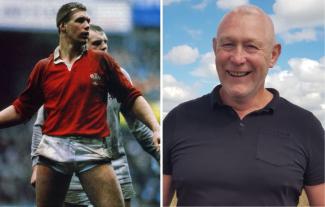

With his autobiography out now, former rugby international Mark Jones gives us a summary of how stammering impacted his on-pitch behaviour.

It wasn't until the age of six that I became aware that I stammered, and being much taller than other children made me stand out even more.

Over the next few years my stammer became a real issue so my parents arranged some speech therapy, which was very basic — just reading aloud from a book, which I found very difficult and didn't make much progress. It was around this time I was targeted by some of the older boys and bullied about my stammer, which made me very frustrated and deepened my insecurities.

My struggle to speak made me a loner during my teenage years. I found it difficult to function when it came to conversing with people. I felt anxious, angry and hated myself. Unfortunately, my frustrations spilt over into everyday life and I started misbehaving and finding myself on the wrong side of the law.

My escape

My self-esteem was non-existent and I desperately needed something to help build my confidence. Fortunately, a local rugby club established a junior section which quickly became the centre of my life and the way to physically release the frustrations and self-loathing that had built up inside me. Although I was tall, I wasn't the bravest but I discovered that I loved being part of the team. More importantly, for the first time in my life I was part of something — I belonged. I could express myself without the need to speak, and playing for the team was my form of conversation.

Rugby was my escape from the awkward schoolboy who could hardly speak. I was quite good and getting noticed in the team, so I concentrated on becoming even fitter and stronger. Maybe one day I could play for Wales, I thought. I became totally focused on the thing that made me feel good about myself — rugby.

I could express myself without the need to speak, and playing for the team was my form of conversation.

By the mid-1980s I was promoted into the senior ranks and I won my first international cap aged just 21. This was the pinnacle for me, a working-class boy with a stammer was playing rugby for Wales!

Spending long hours in the company of the hardest of men can be challenging. The verbal 'banter' and 'sledging' was extremely brutal and having a stammer made me an easy target. My defence was to go on the attack, by becoming a larger-than-life character. I became loud, big and brash, deflecting any abuse by being even nastier. I got my retaliation in first.

Article continues below...

Unleashing pent-up emotions

Looking back, I can now see that this over-the-top behaviour had a dark side, because I was unleashing all my pent-up emotions on the opposition. It was brutal and that side of my character took over. As my dubious reputation grew it generated more attention which I equated with success, but it wasn't — I can see that now. My on-field behaviour spiralled out of control and I was caught in a trap from which I couldn't escape, even if I'd wanted to. But at that time I loved the notoriety. The more anger I had, the worse I behaved and the more attention I got. I was ashamed of my stammer so the news I generated for my brutality deflected attention, so I kept doing it. I made the wrong choices far too often but that didn't matter to me at the time. My notoriety as a player meant no one noticed I could hardly speak.

I started anger management counselling which quickly revealed the connection to my stammer.

This destructive path couldn't continue and, after one very unsavoury incident which fills me with guilt and shame, I was told I'd never play for Wales again — I knew this behaviour had to end. I desperately needed help.

Speaking honestly

Thanks to some very special people who knew I was at my lowest ebb, I started anger management counselling which quickly revealed the connection to my stammer. The next step of my journey was to have another go at speech therapy, which transformed the way I thought about myself. I gradually became more fluent and I learnt to do the things other people did, like answering the phone and being able to say my name, but I knew that until I stopped trying to hide my stammer, the battle would continue forever.

That was when I made a decision to speak honestly to people about my stammer. To my great surprise, my friends made me realise it was a far greater issue to me than it was for them. That was a huge mental weight off my shoulders. I'd spent 50 years trying to hide my stammer and now I knew I didn't have to — I relaxed and now have no fear of speaking.

My stammer is still a part of me but it doesn't define me. I'm no longer ashamed of it and I know that I can control it. The days of it controlling me have long gone.

You can read Mark's story in more detail, including how therapy helped transform his outlook, in his autobiography 'Fighting To Speak: Rugby, Rage & Redemption', out now. Read a review of the book from a member of our volunteer review team.